|

11 Money |

A quick recapitulation: in Segment 3 we noted that self-owning human beings, free to do as they please, will normally choose to interact with others so as to enhance their styles of life, and do so under terms of contracts which are explicit and voluntary, even if they aren't always written down. That's a "market" and it's what a free society would be.

So as to make it easy to exchange things and services, we also saw that "money" would normally be used - but didn't pause then to define or examine money. We will now, here in Segment 11.

Ease of exchange is important, because if it's not easy it involves a cost, of time or effort; call that a "transaction cost." You might want to acquire a pair of shoes, but the shoe retailer accepts only tenderloin beef that day, and you happen not to own any beef. So both of you have to make calls and negotiate to see how to solve the dilemma and get the shoes on your feet and the beef in his freezer. Much simpler if there were a medium of exchange which is universally acceptable; the transaction can then be completed in a few seconds and at negligible cost.

That medium is "money" and in history it has taken many forms; early trading between English colonists and Pequot Indians in the 1600s was done with wampum, a variety of bead. Money can consist of anything which is valued by everyone in the market; "valued", for everyone trading will be handing over something of value - the product of a day's labor, perhaps - so he must feel assured that the token he's receiving in exchange will, in due course, be exchangeable for something else he may want to buy. Thus, whatever is used for money must be:

- Intrinsically valuable upon receipt, and

- Able to keep that value over time

Wampum didn't last, because it was too easy to counterfeit; it took less labor to forge a set of beads than to produce something truly valuable like a coat or a bushel of wheat. That tells us of a third requirement for sound money: it needs to be rare and therefore unprofitable to counterfeit; the cost of producing it must be comparable with its value in exchange.

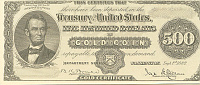

The most frequently chosen medium of exchange, in 5,000 years of recorded human history, has

been gold. Gold has had a couple of disadvantages,

as money: it is a dense metal and so rather heavy to carry around, and so rare and valuable that

it's difficult to divide into small portions, to exchange for small items such as a loaf of bread. Those

shortfalls have been handled by using silver for such small purchases (but then complexity arises

- as it did in late 19th Century America, which used both metals - when the exchange rate

between the two changes, as it will do in obedience to the natural law of supply and demand in a

free market.) Another way to overcome the difficulty has been to issue gold certificates in

small denominations - though there the problem of counterfeitability resurfaces. Today, thanks to

the Internet, neither of those partial solutions is needed because gold-based accounts can be run

with high precision and even tiny quantities can be exchanged;

E-Gold was the pioneer, in 1996.

The most frequently chosen medium of exchange, in 5,000 years of recorded human history, has

been gold. Gold has had a couple of disadvantages,

as money: it is a dense metal and so rather heavy to carry around, and so rare and valuable that

it's difficult to divide into small portions, to exchange for small items such as a loaf of bread. Those

shortfalls have been handled by using silver for such small purchases (but then complexity arises

- as it did in late 19th Century America, which used both metals - when the exchange rate

between the two changes, as it will do in obedience to the natural law of supply and demand in a

free market.) Another way to overcome the difficulty has been to issue gold certificates in

small denominations - though there the problem of counterfeitability resurfaces. Today, thanks to

the Internet, neither of those partial solutions is needed because gold-based accounts can be run

with high precision and even tiny quantities can be exchanged;

E-Gold was the pioneer, in 1996.

Those shortfalls having now been overcome, nothing (except government!) obscures the outstanding natural advantages of gold as money:

- It has a high intrinsic value, being beautiful and malleable and popular in jewelry

- It has proven over thousands of years to keep a remarkably constant value, and

- It is very rare and quite hard to extract from the earth and impossible to counterfeit

1. Government "Money"

We've seen above something never taught in government schools: a brief account of what money is, what purpose it serves, what requirements lie upon it and why gold has been and probably will continue to be the favorite form of money in human society. Now let's turn to what prevails today in America and throughout the world; for what is everywhere seen as "money" is: paper!No society in its right mind would choose paper for money:

- It is intrinsically almost worthless

- Again and again, it has proven to lose its nominal value over time

- It is quite easy to counterfeit

Paper appeared as a convenient form of money much earlier than 1913 - but only in the form of

certificates for gold or silver, issued by banks which placed their reputations and businesses on

the line when they had them printed, and which the holder could exchange for metal upon demand of the

issuing bank's teller; the US Treasury issued some too. So people got used to carrying paper as money for more than a century, and most Americans did not notice or understand what was happening when gradually the connection between paper and metal was broken. FDR savagely attacked it in 1933 by

prohibiting

individuals to own gold other than jewelry but it was not completely severed until 1971, when President

Nixon declared that the value US Dollar was no longer even nominally guaranteed in terms of gold.

Paper appeared as a convenient form of money much earlier than 1913 - but only in the form of

certificates for gold or silver, issued by banks which placed their reputations and businesses on

the line when they had them printed, and which the holder could exchange for metal upon demand of the

issuing bank's teller; the US Treasury issued some too. So people got used to carrying paper as money for more than a century, and most Americans did not notice or understand what was happening when gradually the connection between paper and metal was broken. FDR savagely attacked it in 1933 by

prohibiting

individuals to own gold other than jewelry but it was not completely severed until 1971, when President

Nixon declared that the value US Dollar was no longer even nominally guaranteed in terms of gold.

In the 35 years following 1971, the paper US Dollar lost 77% of its purchasing-power value.

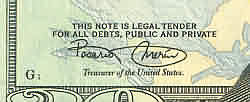

Obviously, nobody would volunteer to use such a flimsy excuse for money; its use had to be compelled, as well as to be introduced gradually so as to deceive the population into supposing it represented something real. The key is the innocent-sounding "legal tender law." On its face, any US bill (or rather, "Federal Reserve Note", as it says at its head) declares "This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private." Many suppose that to mean, it's okay - you can go ahead and use it, the government guarantees it's good.

That law means no such thing. It really means "Sucker, you are legally forced to accept this in payment,

like it or not." Hence the term "fiat money", meaning "money is what we say it is."

Bad "money", by force of government law, has excluded good money.

That law means no such thing. It really means "Sucker, you are legally forced to accept this in payment,

like it or not." Hence the term "fiat money", meaning "money is what we say it is."

Bad "money", by force of government law, has excluded good money.

It's worth pausing to notice the importance of this, for there are many good people who mistakenly blame the Federal Reserve alone for the debasement of the US Dollar, as if its whole cause was the participation of that private association. The very opposite is the case!

Imagine that as a large club of private banks, the Fed issued its Notes as today, without any pretense that they certified anything such as exchangeability with gold, but that there was no legal-tender law - no government force, to make creditors accept them. Would they accept them then? - not in a million years. Especially not when they saw that the notes lost value every year!

It gets worse. Part of the scheme that binds the Fed to the government is a sweet deal called "Fractional Reserve Banking." This means that it's quite okay for a bank to lend out money it does not have, and earn interest on it. If it receives a deposit of $100, it is free to lend out $90 (currently) and when that's re-deposited, a further $81, and so on to a total of $900 - to borrowers who might pay 5% a year in interest on the $900, which (with the full knowledge and approval of the Fed and the US Treasury) it "created" out of nothing. That would be $45/yr, or 45% on the original $100 that it does have, on deposit. The deeper we look, the deeper the fraud!

That's a "fraction" of 1/9, or about 11% - it varies from time to time. In essence, banks are allowed to keep in reserve only 1/9th of the money they lend out. Now, absent government (ie in a free market) would you deposit your money in an institution that loaned out 9 times what it held? No way, José!

Take it a step further, and assume that in such a free market, Bank B noticed your reasonable reluctance and advertised that they loaned out only 5 times their (actually, your) deposits, instead of 9. You would find that much safer, so you might make a deposit; Bank B would compete effectively with the first bank. Then along comes Bank C, announcing a Fractional Reserve of fully 2/3 of its loans; you would probably switch to that one, as being safer yet. Finally comes Bank D and does it right: 100% in reserve! It lends out nothing it does not possess (though it may make some charges for its service of keeping your money in its vault.) That is about as safe as one can get. So you and everyone else would prefer Bank D, and all those practicing Fractional Reserve would go out of business. In a free market, good banking practice would drive out bad.

By that logic is proven the proposition that Fractional Reserve Banking, with all its attendant evils, can operate only when the market is not free - when government controls it. The hands of the Federal Reserve are hardly clean; but the essential ingredient of the fraud is the set of government laws that force the population to interact with it in ways the free market would not touch with a ten foot pole. The Fed is an accessory; government is the master criminal.

Now let's see why governments go to all this trouble.

2. Inflation and Control

The reason governments love paper and force its use upon those they control is that it's so easy to print. And why is that so attractive to them? - see if you can guess:

As Professor Rothbard details in "What Has Government Done to Our Money?" (see foot of page) the printing of money by government need not be literally the cranking of a press. Huge blocks of "money" are created out of thin air by a very sophisticated, fraudulent process: the US Treasury offers to sell a "T-bill" with a face value of (eg) ten billion dollars and the Federal Reserve Bank buys it, at a discount that provides part of the motive to do so. The trick is that at the instant of purchase - writing the check - the Fed does not have the money! Instead they "kite" the check until the next day, when the T-bill is deposited in the account, so "balancing" the books. The result gives the government cash to spend, while it gives the Fed an asset that it can use to lend out to borrowers such as home buyers and expanding businesses - at interest!

Everybody wins, especially borrowers who can pay back loans with cheaper "dollars" - such as government with its $6 trillion debt - but not the holders of the "money" with a value duly diluted by that chicanery; ordinary people, and especially those conned into buying government CDs earning less interest than the inflation rate. Government savagery is not always done by thugs in Ninja suits; sometimes the suits have pin stripes. But there's even more.

3. The Dollar Empire

In stunningly beautiful Bretton Woods, NH there met in 1944 delegates from 45 nations (Germany and Japan were

not invited) to agree what would replace the British Pound as the world's "reserve" currency. No prizes for

the answer: it was to be the US Dollar, since the UK and most other countries were nearly bankrupt due

to the war still raging. The Feds promised to exchange gold for dollars at the rate of $35

per ounce; a promise that Nixon broke in 1971. But by then the dollar reigned worldwide.

In stunningly beautiful Bretton Woods, NH there met in 1944 delegates from 45 nations (Germany and Japan were

not invited) to agree what would replace the British Pound as the world's "reserve" currency. No prizes for

the answer: it was to be the US Dollar, since the UK and most other countries were nearly bankrupt due

to the war still raging. The Feds promised to exchange gold for dollars at the rate of $35

per ounce; a promise that Nixon broke in 1971. But by then the dollar reigned worldwide.

By "reserve" and "reigned" is meant that the US would act as the world's banker; that capital goods and commodities would normally be priced in terms of the US Dollar. Thus, if a Brazilian order was to be placed for a hydro-electric dam with contractors from Japan, money would flow in the form of dollars. The supply of dollars to be held for international trade has meant (ever since 1944) that American "money" has been the world's currency. This has had two consequences for Americans.

First, it has brought prosperity we have not earned. Because of the special status of the dollar, foreign

manufacturers are willing to export to buyers here useful goods such as automobiles, oil and TV sets, and

to accept in exchange pieces of green paper; or more accurately, electronic entries in an American bank

account. They then invest those bank balances in US Government IOUs (bonds, to be repaid eventually by US

taxpayers at the point of a gun) and in shares of US companies.

The net effect is that US residents enjoy a steady flow of useful goods with no corresponding export of

other useful goods or real money such as gold, but also that foreign investors gain an increasing degree of ownership in those companies. That's the price we pay for such prolonged though

artificial prosperity. When the government's power to tax evaporates a few years hence when all

Americans, then better-educated, walk away from government, there will be a lot of unhappy foreign

investors; perhaps a few truckloads of $100 bills will be printed up to satisfy their contracts, but nobody

here will accept them any longer in exchange for anything valuable. Those "legal tender" laws will be no

more

Second, it has meant that to keep tabs on the ocean of US money that is circulating around the world, the Feds have had an excuse to probe in every country to see who owns what; their scrutineers don't just demand that US domestic banks deliver private bank-account information upon request, but that even foreign banks do likewise, if accounts are held in dollars. This has severely hampered the ability of Americans to place their own money out of reach of the taxgatherers; financial privacy, worldwide, is but a sick joke. Cynics say the "golden rule" is that he who owns the gold, makes the rules; since 1944, the US Government has proven that he who prints the dollars makes the rules. America is increasingly detested worldwide as a result, giving motives for future wars. But the government's gigantic thirst for power is slaked... for a while.

4. Segment Review

Here then is what we've learned, in brief:

| Real money is whatever a free market chooses - nothing else; while government paper is literally "monopoly money" which it uses to extend its power - abroad as well as domestically - in a wide variety of ways. The result has been and continues to be a destruction of the value of its currency (inflation) and a gross distortion of all economic activity - hence a depressed standard of living - and a near-total loss of individual privacy. |

We've all grown up to understand that "money" consists of bits of paper headed "Federal Reserve Note" but in Segment 11 we've seen that it is no such thing and that the implications are awesome. This calls for a huge adjustment of thinking. Don't hurry away, but spend time in the "Further Reading" materials to make sure this information is well absorbed. And first, attempt as usual some closing Q&As, discussing any difficulty with your Mentor.

For further reading:

The Gold Standard

Bubble-Gum Money

Aid to Dependent Dictators

The Fed's Grasping Invisible Hand

"What Has Government Done to Our Money?" by Murray Rothbard